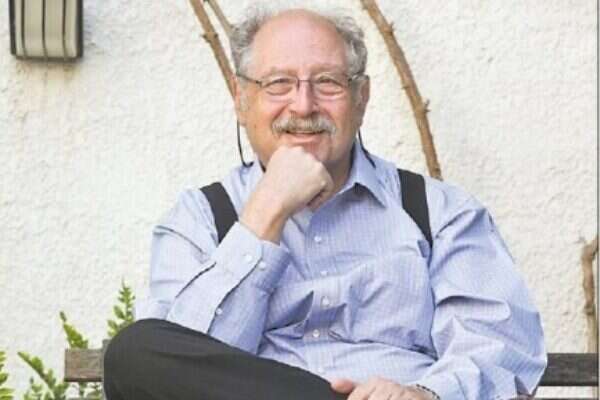

No name is more synonymous with the Israeli high-tech revolution than Yossi Vardi. Vardi was a pioneer in the industry, starting ATL-Advanced Technology Ltd., one of the country's first software houses, in 1969. Since then, he has started or been an early investor in more than 100 companies, by some counts, involved in the internet, telecommunications, energy and cleantech industries, and much more. Among these was Mirabilis, co-founded in 1996 by his son, Arik, which developed ICQ, the first instant messaging program for the internet. Less than two years later, Mirabilis was bought by AOL for $407 million, inspiring a wave of internet entrepreneurship and helping to transform Israel into the Startup Nation. Vardi has also served in a number of senior government positions, as director general of the Development and Energy ministries among other esteemed posts. He served on the boards of many public and private corporations and universities, was chairman of the Jerusalem Foundation and participated in negotiations on peace, regional cooperation and economic development with Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and the Palestinian Authority. I met with Vardi last week at the 2016 Forbes Under 30 Summit, which brought together young entrepreneurs from America, Europe, the Middle East and Africa. The summit was an extension of Forbes magazine's annual 30 Under 30 list, which identifies 30 of the brightest young entrepreneurs, talents and change agents in each of 20 different sectors, such as consumer technology, media, and education. Chatting over lunch, I peppered Vardi with questions on the high-tech industry as well as more general socio-economic and political issues. Vardi's sharp, direct answers demonstrated why he remains the "godfather" and guru of Israeli high-tech and a much sought-after adviser in both the private and public sectors. Q: How is the new generation, the new under-30s, different from previous generations- "If you look at the high-tech ecosystem, it can be divided roughly into three levels. The first level is the digital immigrants -- people who were analog most of their lives. Today, they are around 55 and up. They are the investors. "The second level is the digital pioneers. They were analog when they were young, but by the age of 15 or 20 were digital. They may remember rotary phones, but most of their lives they used push-button phones. This is the 'desert generation' [an allusion to the Israelites wandering in the desert after the exodus from Egypt]. They are ages 35 to 55. They started the internet 20 years ago. Today they are in managerial positions. "The third level is the digital natives. They were born into the computer age, and began using personal computers from the age of 2. Today, when they see a picture in a magazine, they try to swipe it like a cellphone. They never saw a rotary phone. They represent the cutting edge of technology. "Understanding these strata, this structure, is key to sourcing good technologies and good executives." Q: It's a unique situation that will never return, isn't it- "Yes. Twenty years ago, the executives were digital immigrants, and still analog, and those in the desert generation were the product people. And because the executives didn't understand what was going on, the Yahoos and Googles were able to step into the place of the huge media monsters, who were resisting change." But this is no longer the case. As time passes, fewer and fewer technology experts, entrepreneurs, executives, and even investors will remember the analog era. "That's why people are excited about the 30 Under 30," Vardi explains. "They are our future, and they are all digital natives." Q: Is entrepreneurship something that can be taught or do you have to be born with it- "It cannot be taught; it can be unleashed. There is a big difference. An ultra-Orthodox Jew or an Arab Israeli or someone from the periphery who is very entrepreneurial has no opportunity to access the high-tech market. The barriers to entry are too high. And entrepreneurship doesn't belong to a certain level of income or to a certain background. You have entrepreneurs in every community. There is the guy who provides services and the guy who provides transportation and the guy who opens a grocery. All of these are entrepreneurs. In different circumstances, they could have been great entrepreneurs. Never mind that they came from humble beginnings. The question is how to unleash their entrepreneurship and provide them with opportunities." Q: You've sat on the boards of many universities. With so many new frameworks for education opening up, do you see the role of universities changing, particularly in the area of technology- "The role of the universities is changing, but some of the core functions of the great institutions of higher education will continue. For example, in order to do research, you need laboratories, you need faculty, and this will definitely continue, though frontal education may change. "But what is more interesting is the number of new disciplines that are opening up compared to 10 years ago. For instance, algorithms became a very important discipline. For many years, algorithms were just one of the many disciplines of mathematics. Today, mathematicians dealing with algorithms are the single highest-paid sector in internet [businesses], all over the world. Who would have thought that the mathematicians would be king- "Also, another thing that is very important: The phenomenon of the internet opened an avenue in high-tech to many people who were not necessarily coders. You need to tell a story, you need to do a design, you need a compelling page. So it opened a wide opportunity to people who were not traditionally regarded as high-tech. "And the very good institutions of higher education are providing something that is not easy to replicate. You know, if you have a Ph.D. from Stanford, you have a good chance of being hired by Google." Q: Israel is more materially developed and comfortable than ever before. Does this material comfort reduce one's entrepreneurial drive- "There's a big fallacy in what you say. I want to set you straight. This material comfort affects less than 10% of the country. I always say this is not a startup nation, it's a startup fraction. For 90% of the people, the whole thing looks strange. Only 8.7% of the workforce is involved in high-tech. For this 8.7%, yes, life is terrific." Q: Does high-tech increase or decrease the gaps between rich and poor- "High-tech does two contradictory things. First, when the tide comes in, all the boats rise -- even the boats of the poor people. This was demonstrated in a recent publication by [Tel Aviv University Professor] Dan Ben-David. He provides very good statistics. On the other hand, some boats rise more than others, so the gaps increase. High-tech raises the bottom, but it raises the top much more. In Israel, because of the dominance of high-tech, the gaps are the highest among the Western world. "Now, because this industry is regarded as a Tel Aviv industry, though you find it also in Herzliya, a little bit in Jerusalem, and in Rehovot, I think this is one of the reasons for the alienation between Tel Aviv and the rest of the country." Q: The Knesset just passed a law that caps the salaries of banking executives at 2.5 million shekels (around $660,000) or 44 times the salary of the lowest-paid employee. Does this make sense economically, and will it help reduce the gaps between rich and poor- "Yes, for sure it will help. But I think it is more symbolic than anything else, because really, how many people does it affect? But sometimes symbols play a role." Q: Are we making strides in getting the ultra-Orthodox and Arabs into the high-tech workplace- "Let me start with a very strong suggestion or observation: I think that the only solution to many of the problems that we have here is what I call radical inclusion." Vardi goes on to describe how Israel is divided into different communities, each of which believes its own narrative. "And there is no need to try to agree on the narrative. People will never agree because everyone is right from his own point of view. What we should try to do is agree on a vision of a shared future. We should say: 'We cannot reconcile between the narratives. But what we can do is try as much as possible to converge around a vision of a shared future.'" Q: Does this shared future include Palestinians and our other neighbors- "No, I'm talking about within Israel. With the Palestinians, I think we should make peace. And the sooner, the better. And there is no scenario for peace that meets all the aspirations of the two parties. But within Israeli society, what I call radical inclusion is the solution." Q: Can you comment on rumors about increasing business ties between Israel and the Arab world, for example in the Gulf states- "I don't know about it. But for sure, the Middle East is totally different, and Europe is different from what it was five years ago, in a very profound way. And there are major opportunities and major risks. I think it's a very exciting time." Q: Exciting? It seems very insecure. "On the one hand. But on the other, it may be a time to reshuffle the cards. There are conflicts within the Arab countries that put us on the side of some entities and in conflict with others. The map is also being rewritten in the Far East. I think in 20 years, China will be the dominant power in the world." Q: Do you see the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement as a threat to Israel, and in particular to Israel's high-tech industry- "I'm not at all concerned about the economic effect of BDS. We have been subject to boycotts before. I've always said the two founders of Israeli high-tech are [former French President Charles] de Gaulle [who declared an arms embargo against Israel three days before the outbreak of the Six-Day War] and the Arab boycott. "But I'll tell you the main problem with BDS: It provides a very low barrier of entry to people who want to delegitimize the State of Israel. If someone throws [Israeli] bell peppers on the supermarket floor, the damage is not the few dollars that they cost, but the fact that this shows his objection to the State of Israel. It's much easier to mobilize people to do this than to attend some intellectual discussion on the occupation. BDS is a lubricant for people who want to show their reservations about the State of Israel." Q: What about the argument used so often in public diplomacy, that if you support BDS you'll have to throw out your computer and cellphone since they are full of Israeli technology? Is this argument compelling or silly- "I think it's not an argument at all. I think that you have to deal with the issue, with what the occupation is leading to, and what you have to do to maintain the occupation."

'The solution is radical inclusion'

Yossi Vardi, considered the godfather of the Israeli high-tech industry, says entrepreneurship "cannot be taught, it can only be unleashed" • He insists that the divided Israeli society must "agree on a vision of a shared future" if it is ever to unite.

Load more...