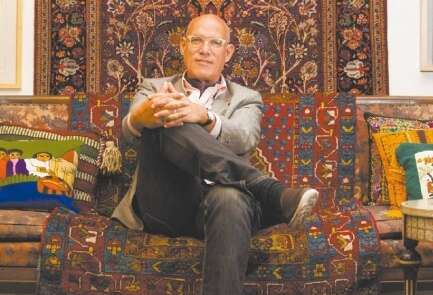

It was Jewish German-born American philosopher Hannah Arendt and German poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht who made Haaretz columnist Benny Ziffer lose his train of thought this week. At the beginning of April, Ziffer had planned to focus his weekly column on the back page of Haaretz on Turkey and its President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, but at the request of his editors he agreed to switch course and write about an interview given by singer Eyal Golan to Channel 2 that week. In 2014, Golan was investigated on suspicion of soliciting sex from underage fans, but was ultimately never charged. It was under these circumstances that Ziffer ended up writing the now infamous column in which he voiced his understanding for great artists' need to have "intercourse with young female admirers. Without this, there would be no creativity, for all the pain this is liable to cause these young women, whose lives might have been damaged." So what does the massive public outcry that this column elicited have to do with Arendt and Brecht? "Sometimes it is not good to read books," Ziffer, 63, explains in an interview with Israel Hayom. "I was under the influence of a long essay by Arendt, in which she analyzed Brecht's character. Brecht was an insufferable man. He was disloyal and hurtful. In her essay she writes, similarly to what Goethe argued, that artists aren't treated like other regular mortals -- they are afforded special privileges. She didn't mean that they should be given privileges but rather that this is the reality. That is what I was trying to argue." Q: With partial success, at best ... "I was misunderstood. It was one of those times when you write something because you were asked to write it and you trust that more people will read the text after you submit it. You trust that there will be additional filters. But whoever read that column didn't find anything wrong with it. What did I say that shocked everyone so much? Take Woody Allen, Roman Polanski, or artists who sympathized with the Nazi regime, like poet Ezra Pound. They all did immoral and illegal things, but in the context of their artwork, they were entirely forgiven. "I find all the time that artists are usually completely egocentric people. The moment they want something they become like children. They have no moral deliberations. I don't see this as something positive, but it is the case. That is how I should have put it [in my column]." At first, Ziffer didn't realize that his column had set off a volcanic eruption that was about to scorch the earth. "On the weekend that the column came out, there were the regular protests, the kind I'm used to. There was no controversy," Ziffer recalls. "Two days after it was published, it was a Sunday, the Haaretz Culture Conference was held. The hall was packed. When I go on stage to oversee the starting panel I was booed, as if I were at least [Culture Minister] Miri Regev. One of the panelists noted that she had debated whether or not to withdraw her participation in the panel. I still didn't quite understand that things were getting out of hand. I was completely arrogant and headed the panel the same way I always do. Later, people walked past me and looked at me with rage. There was even one woman who hissed at me, 'You are a disgusting human being.' I was really hurt. "The next day, I opened my copy of Haaretz and read about the protest letter, signed by poets and poetesses, calling to boycott the poetry festival in Metula for which I serve as artistic director. Suddenly I began to realize that things were headed in a bad direction. Do they really hate me that much? Something must be wrong with me. "That Tuesday, late in the morning, I was sitting in the library at Sapir College where I teach writing and journalistic editing. There was a television crew on its way to interview me, to get more of my response to the affair, and I suddenly realized that I was just adding fuel to the fire, while my audience and my peers, meaning the participants in the Haaretz Culture Conference and the Israeli poets, all hate me. I didn't understand where I was or what had happened. I was dealt a sudden, painful blow." In the middle of the night that Tuesday, Ziffer sat at his kitchen table in his Raanana home and diligently wrote an apology column. "Within the newspaper, the support for me never waned, but still I called the editor-in-chief Aluf Benn and informed him that I was quitting the column. I felt like I was losing control." Q: Was it entirely your decision, or the paper's- "People made up stories about the editor summoning me for a hearing, or that it was decided to take my column away -- no. It was my decision. I decided that this would be my last column. I had never received such a negative response, despite all my provocations. In those moments I felt like I had become the bad guy and I had an earnest need to apologize." Q: In your apology column, you describe yourself as a satanic clown that had reached the "height of monstrosity." Was your apology authentic- "I know that if you want to do something meaningful and have an impact, you have to play the part. I wanted to apologize, but the apology column was written in a calculated manner. Not straight from the heart into the computer. My feelings underwent artificial and stylistic processing. I believe with all my heart in the Paradox of the Actor by French philosopher Denis Diderot: If an actor takes the stage and acts out a fight with his wife in the same way that he would fight with his actual wife at home, it would look terrible. Like a caricature. Paradoxically, in order to appear authentic, you have to pretend. Play a part. That is what I have done all my life. When I have something to say, I say it artistically. I don't just transfer a thought onto paper like everyone else." Q: Do you still stand behind your apology? "Well, in hindsight, my message is 'what's the big deal'? So I wrote one column that was offensive and badly worded. That's the long and short of it. I could have written similar ideas and just chosen my words more carefully, more substantially." Q: But then you would not have enjoyed all the commotion around you. "Obviously I enjoy drawing attention and sparking interest. What I care about as a journalist is always being interesting and interested, and in order to do that I have to throw myself into the ring. You can't just write, you have to almost be a reality show. And I have plenty to give. My message and my worldview are unique in that, as a leftist Haaretz staffer, I shake up the ostensibly politically correct discourse and put things into the right perspective. Recently I have ventured out, and I really liked it." Q: What did this venturing out entail? "The moment I went to visit [Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's wife] Sara Netanyahu at the prime minister's residence about a year ago. I wanted to publish an interview with her in the student paper of the Sapir College Culture Creation and Production Department. I wanted to take my students and go for the biggest thing there is. Much to my surprise and great pleasure, she did not reject me and actually invited me over for a 20-minute introductory meeting, which ended up lasting three hours. At Haaretz, everyone told me: 'she is going to leave you hanging. She'll make you wait for hours and then dump you after ten minutes.' But she came to our meeting exactly on time, to the minute, and she was really nice, intelligent and fascinating. We developed a chemistry and mutual trust." After writing an op-ed expressing his admiration for Sara Netanyahu last February, Ziffer was bombarded with a combination of boundless sympathy and contempt. "On the one hand, people stopped me on the street to thank me and taxi drivers refused to take my money as a sign of appreciation. The public, the people, were ecstatic. They said to me, 'Finally, someone is talking. What a brave man you are for defending Sara Netanyahu.' On the other hand, I was at a restaurant in south Tel Aviv one night when a woman got up and screamed, 'He visited Sara Netanyahu.' Others joined her and called out, 'Yeah, we hate him too.' It was simply insane. It was like I had committed a crime against humanity. That, back then, should have set off alarm bells for me. "When you operate in the home turf of the elite, or those who consider themselves the only ones who know the right way to think and the right things to believe, you will be inevitably be attacked if you dare to think something different. The one person who foresaw this was sociologist Eva Illouz. She told me, 'You broke a taboo in Israeli society.' It was good that I broke this taboo. I exposed the insanity and lack of proportions that were still sky high when I met the Netanyahus a second time. "After the election [in March], Sara Netanyahu thanked me profusely for defending her and invited me over for dinner. I thought that it would be better if they came to our house. The truth is that my culinary experience at the Prime Minister's Residence was not very exciting. There was definitely room for improvement, let's put it that way. And again, I was told that they would never come, what are you thinking? But it happened. We set up a little buffet in the corner of the living room, and opened the windows and balcony doors wide. The security guards remained outside and even the street wasn't closed off. I also invited [writers] Eyal Megged and Zeruya Shalev who are mutual friends and to embellish the dinner party I invited Nehemia Shtrasler, Prof. Yigal Schwartz and his wife and Yuval Noah Harari and his partner. We had a lovely evening. It was enjoyable and interesting." 'The Western occupation gives them hope' Ziffer lives in a home that perfectly suits his personality. It is a two-storey building in a small alleyway in Raanana, where wild flowers grow and cover every corner. The inside of the house is bountiful, on the verge of exploding. There are knick knacks everywhere and the furniture is a mix of east and west -- tempestuous Orientalism intermingled with European elegance. The embroidered cushions, hand-made rugs, dolls, sculptures and the countless pictures on the walls deal a strong wallop of color as you enter the house. Books are also very prominently present, of course, in quaint little piles in every corner and on shelves. Ziffer was born in Tel Aviv to Heinz, an electrical engineer, and Nira, a doctor. He deferred his military service to earn his academic degree in French literature at Tel Aviv University, and then served as a training coordinator in the IDF. For the last 30 years, he has been the editor of the Haaretz literary supplement, and has written columns and articles for the paper. He has written five books and translated various French writings. He is married to Dr. Irit Ziffer, an archaeologist at the Israel Museum, and has two sons and one daughter. He has one grandson. As is his habit, he greets me wearing an evening jacket, a cloth handkerchief carefully wrapped around his neck. "I don't dress like this around the house," he remarks. "I only greet guests like this." Our meeting coincides with the publication of his latest book, "To Heaven with the Donkeys." The name is borrowed from a poem by his favorite French poet, Francis Jammes, "A Prayer to Go to Heaven with the Donkeys." In the poem, the donkey represents a simple, weak animal, and Ziffer, too, aspires to "return to the simple, clean, unsanctimonious point of view of the people." He says the book "describes a process of a drastic transformation from a world that seemed sane to me, and that I could live in, to a world that became increasingly violent. A shift from a place where it was possible to play intellectual games and voice different opinions to a place where there is no room for dialogue." The process of writing the book involved a look back on columns that he had written in recent years and combining them into three different journeys. The main journey is one in Israel. The second journey is to Turkey, where his parents grew up and where he has visited often, and the third is to France, as worthy of such an avid Francophile. The journey in Israel, he explains, is "a journey of disillusionment from the leftist lifestyle and way of thinking." This journey reveals Ziffer's contempt for the Tel Aviv culture and the "self-righteous" Israeli Left. Q: Do you take issue with the ideological foundations of the Left or with their style? "Essentially, I agree with a lot of the ideology -- things like equal rights and the like. But there are also the people, and I have a big problem with them. The Left isn't really liberal. It is only liberal as long as you don't oppose its views. "Also, ideologically speaking, I feel that the Left is disingenuous with the slogans it disseminates. 'Stop the occupation,' for example. That's not realistic. It's a bunch of bull. This week I went to [the Palestinian village of] Bil'in with my wife after we hadn't been there for a long time. You go past the checkpoint and you see Modiin Illit and Kiryat Sefer, which have expanded to the point of touching the neighboring Palestinian villages, and you see some of the villages, which used to be dirty, God-forsaken hell holes, thriving and flourishing." Q: Do you credit the settlements for that? "Yes. People go there to have their cars fixed at garages, to get dental work done at dental clinics. They opened a commercial center there. There are Jewish clients. Peaceful coexistence is an inevitable byproduct of all this occupation-shmoccupation stuff. Life is stronger than any slogan. The existing model actually works." Q: Do you think it works to the point of a binational reality- "The Palestinians would be very pleased to live in a modern country like Israel where they can enjoy all the social benefits and good things that a welfare state provides, and where they would be given the freedom to practice their religion and observe their culture. They want something that is impossible. They want sovereignty on the one hand while enjoying all the privileges of a welfare state on the other hand. But the moment that happens, the country will go to hell. It will be chaos." Q: Is that what your close friends in Bil'in tell you? They don't want a Palestinian state- "The Palestinians are incapable of running a state. The corruption there is horrendous. The leftist organizations know it too. The occupation as it is now can last forever, and it is better than any alternative. "Our friends in Bil'in prefer standing at checkpoints and jumping through hoops for permits to work in settlements over working for their own brethren in Ramallah. In Ramallah they are treated like dogs and get paid 50 shekels [$13] per day, of which 20 shekels are spent on getting to and from work. It is such a decadent and corrupt society. On the other hand, in the settlements they are paid 250 shekels per day, they receive food and clothing, and they get served coffee and tea -- they are treated like human beings. Most of the people in the settlements are very nice to them. "The desire to separate the two peoples is atrocious on a humane level. How can anyone think that a people with the ability to breathe under the Israeli occupation will one day be under the rule of an oppressive, primitive and corrupt Palestinian state that could easily turn into an ISIS state? The Palestinians will never come out and say outright that this is their preference. There is close social monitoring among them. But you can see these things in their eyes. It is the Western occupation, of all things, that gives them hope. "There are so many leftists who have never set foot in these places and have never seen the reality up close. I understand that there is a dilemma, that there are people who don't visit the Palestinians in an effort to avoid colonialism or 'enlightened occupation.' I think that the current reality is not bad at all. The standard of living is good. But when I say these things to my colleagues at the paper or to my friends, they laugh at me." Q: Because it sounds very paternalistic. "Fine, well, but that's the way it is. There is not a single place on this globe where Arabs managed to get by without the help of the West." Q: But the Palestinians constantly lament the trampling of their rights. "Come on now. The people inciting the Palestinian villagers to protest are the Israeli leftists. They fan the flames and encourage the Palestinians to protest in the way they protest. Why does it regularly happen in Bil'in and not in other villages? That village has been turned into a symbol. "And say that I'm wrong. That the Israeli protesters are walking hand in hand with the Palestinians who genuinely initiated these demonstrations. The Israelis go to the demonstration and then they return to their homes in Tel Aviv. The Palestinians have to stay and live there. It is true that there have been Israeli protesters who have also been wounded by IDF bullets [in those demonstrations], but after the protest, the soldiers go into the Palestinian village and search the Palestinian homes and make arrests. I don't see a lot of people in the village who want this kind of uprising. Today I am telling you explicitly that if it weren't for the leftists, they would be living their lives in peace. And I'm not trying to stir trouble with the veteran [Israeli] protesters who have been going there religiously every Saturday for ideological reasons." Q: Do you have any criticism for the Right? "The Right has a Jabotinsky-esque majesty to it. There is gentlemanliness, fairness, loyalty. Once you belong to a certain group, you maintain loyalty. You don't rat out its members, speaking of Breaking the Silence. The guiding principle is the old, conservative values. "However, unfortunately, the Right is not quite sophisticated enough. The best example is Israel's relations with the world. We're under attack? Find a way to work it out in a way that makes us look good. Don't be stupid. Pretend you're conducting talks with the Palestinians. What do you care? The Palestinians are also pretending they want these talks. And if dialogue somehow ensues, even better. "It's not like there aren't any sophisticated people on the Right. Take Miri Regev -- she knows how to manipulate the media and use the reality to work for her. There is also Oren Hazan, who is sophisticated in the sense that he understands that you don't need to be decent, kind and good to gain the public's sympathy. You need to be annoying and do the wrong things. I understood that about myself as well. That way people take an interest in you. The sympathy goes to the people who aren't necessarily perfect in every respect. The form is more important than the content." Being hated as a calling In his new book, Ziffer writes: "I never fit into the rigid molds of Israeliness. Only I had no choice but to squeeze myself forcefully into the mold, like a dead body forced into a too-narrow grave, and somehow claim my place there. Back then, I didn't understand that this culture plays only the two-tone tune of either or, of male or female, of left or right, of secular or religious, of Mizrahi or Ashkenazi, or that it scorns nuance, or that it is not actually a culture, possibly an anti-culture. "I grew up in a fortress of the institutionalized Left -- in the Tel Aviv neighborhood of Afeka, and at the Alliance school," he explains. "That is where I started getting the sense that this society, which is so okay, is actually not so cultured because it is always trying to coerce everyone into submission to its line of thought. It can't accept the possibility of anyone being somewhere between the lines. I don't want to be told what I am. I want to be free. I want to be all sorts of things." Q: Your sexuality is confusing. How do you define yourself: Straight? Homosexual? "I don't define myself at all, and I don't want to define myself. On a political level as well, I really hate the Left, but on the other hand I am not a rightist. I don't feel any confusion about my sexuality. I feel good about myself and I know who I am. My role model is French writer Francois Mauriac, who was exactly like this, like me. No one ever knew if he was gay or straight. He had a family and he said but didn't say what he was." Q: You wrote that as a young man, you were "ridiculed, mocked and humiliated every day for being different. For being soft. For being feminine." "Yes. I was a geeky boy who was beaten up. I didn't enjoy my childhood or teens. I wasn't happy socially. That is when I learned that you don't have to do something bad to be hated. It is enough to deviate a little from the norm. "I spoke French as a boy, and it was considered contemptible and I was laughed at all the time. What was even more shocking was that I was a very good student and very polite. I was punished by the children for being a good boy. They never let me be a part of them, and I also never really liked what the young people were doing, like going out and hanging out in the evenings. I preferred to listen to classical music with my parents or read a ton of books. I would borrow books from the Tel Aviv University library and read them while I walked. Anyone who ever saw me would laugh at me. "Everything that I identified in my youth, I see now among adults. Conformity disguised as enlightenment. In my view, be a fascist, be anything, just not a conformist. Stop thinking that you are so original when all you're doing is reciting the same things you saw on television or read in the paper." In his book, Ziffer declares that he observes the religion of "having the courage not to think like the herd." In that spirit, he expresses provocative ideas. For example, referring to Erez Efrati, the IDF chief of staff's security guard who was convicted of very serious sex crimes, Ziffer writes that "what should have been on trial in this affair was the mechanism that generates these super-human mechanized creatures called security guards or VIP guards. You can't expect creatures who were trained to go against their human nature and become robots not to explode one day." Ziffer adds that he is "the last person who will ever judge them." Q: Here, once again, you minimize sexual offenses and attribute them to external circumstances. "I wrote those things on the basis of what I was told by a woman who was in a relationship with him. She explained to me that these people undergo training that turns them into robots. It happens that something breaks down, like a washing machine that stops working. "What would you have me write instead? What everyone else says? My writing is guided by the principle of opposing the two-dimensional point of view of people who state the obvious. Of course Erez Efrati did a horrible thing. But let's look at it from a different angle. My intent is not to justify the act. I am willing to sacrifice myself and turn myself into a hated man in order to fulfill this calling, which is to give people food for thought that is the opposite of what everyone is sure to be true beyond a shadow of a doubt." Q: You continue to employ Yitzhak Laor in your supplement, despite multiple women's allegations that he sexually harassed them. "I support him because he has worked with me for years. We belong to the same generation and we have known each other since our days at university. And also because he is a magnificent writer and poet. So we should let him go because there are allegations against him? What do these allegations have to do with me? If, heaven forbid, one of my close friends should commit murder, shouldn't I defend him? He's my friend. The question is which value you put above the other. "Dostoevsky said that 'the more I love humanity in general the less I love man in particular.' In other words, it is very easy to love the principles, but it is very difficult to look at an individual who may have committed an act, a sin, a crime, and say that he is still a man. Let's keep in mind that no criminal charges were ever filed against Laor." Q: In your book you mock Israeli writers and even describe many of them as rag dolls. "My criticism stems from knowledge. We have convinced ourselves that Israeli literature is so wonderful because it is successful abroad. But why is it successful? Because the world takes an interest in Israel. Israeli literature is not successful by its own right. "Etgar Keret, for example, came along with his simple short stories and the average German reader, who is accustomed to heavy novels and the writings of Thomas Mann, says, 'Wow, what fun. Why don't we have writers like that-' But obviously there will never be a German writer who writes like Keret -- realistic stories that are half jokes in the style of a child. Because if there were, he would be tossed right out. These are things that were done a long time ago, and it doesn't speak to me at all. "If a nuclear bomb should destroy all the Israeli literature written since the establishment of the state, it would not be such a great loss. The vast majority of Israeli writers are puppets who generate work so that people will like them. In the years that the Left was in power, the literature was very institutional and it served the government. When the Right is in power, the writers become bolder. "I am not drawing a broad line and saying that nothing is worth anything. Yehoshua Kenaz, for example, was a good writer. He just didn't deliver the goods that were expected of him. Just as in Israeli cinema, there are two spices that people feel compelled to put into literary works -- the Holocaust and the Palestinians. And we are always the bad ones, having wronged the Palestinians or what not. It is terribly synthetic. So Israeli literature doesn't move me, what can I do. Israeli poetry, on the other hand, does move me. The poetry of Ars Poetica [a group of subversive poets], which I was the first to publish, is wonderful. Or Generation 1.5 of female poets from the former Soviet Union -- they are really good." Q: The poets of Ars Poetica are a little like you, aren't they? They make a lot of noise about a revolution but ultimately cuddle with the establishment. "As real revolutionaries do, they take advantage of the establishment but avoid becoming assimilated into it. They don't compromise. They break boundaries. They are refreshing, innovative, full of freedom. And like me, they have a lot of artillery and can bring themselves to create many things, new, moving, interesting things."