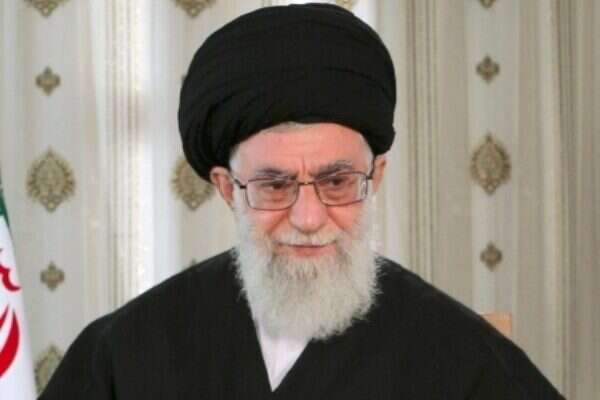

For years, I've made it a point to frequent an old, tiny bookshop in Paris 5th arrondissement owned by an Iranian exile. Every time I visit the French capital, I make sure to pay a visit to this shop, which is replete with books, some of them old. The owner of the bookstore knows that Im Israeli. He also knows the nature of the relationship between his homeland and Israel. A nuclear Iran is a prospect that frightens him also. During my visit there last month, he recommended I take a booklet that was published four years ago and which he had just received. It was a compendium of articles written in January 2008 by Mehdi Khalaji, an Iranian researcher at The Washington Institute for Near East Studies. Its important that every Israeli citizen be aware of what is written in the pamphlet, he tells me. Not only is what he says correct still today, but they have actually gotten worse over the years. In Israel, people need to know that in Iran today there are those sitting in the highest positions who believe that it is permissible to make use of advanced technology in order to bring back the hidden imam, he said. One look at the title, Apocalyptic Politics: On the Rationality of Iranian Policy, convinced me to purchase a copy. At their root, Irans apocalyptic politics are the result of the failure of the Islamic Republics original vision, Khalaji writes. The Islamic Revolution of 1979 began with a utopian promise to create a heaven-on-Earth by enacting Islamic law and establishing a theocratic government. Yet in the last decade, these promises have ceased appealing to the masses, he writes. In light of this failure, the Islamist government shifted tack and adopted an apocalyptic policy, which offers hope to the oppressed. This vision is supposed to be the tonic which will ward off social discombobulation, and it comes at a time when the Islamic Republic is not meeting the expectations of Irans populace, both religious and secular. According to the Iranian researcher, when the government failed to live up to its promises, many Iranians began searching for alternatives. They found them through the worship of the hidden Mahdi (which is translated from Persian as the guided one), who is said by Shiite Islam to be the one who will rule before Judgment Day and rid the world of tyranny and evil. There are a growing number of individuals who to this day claim to be the Mahdi or are in contact with him. The search for spiritual refuge, which in this case comes in its most primitive form courtesy of religion, has created a new world rife with meaning, one in which man has abundant power and supreme significance. This is not limited to religious precepts. This primitive understanding of religion is not just indicative of the behavior and social mores of civic society, but it is also a vital element in the crafting of government policy, Khalaji writes. In this context, there are two figures that deserve special attention: Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The most important person in Iran today is Khamenei, the spiritual leader who has amassed the most experience in the countrys politics. Khamenei is a product of the theological institution of his hometown of Mashhad, which is different from the seminaries of Najaf and Qom. In the 20th century, the seminaries of Mashhad have served as the centers of mysterious scientists and hidden cults, and they were under the influence of anti-rationalist and anti-philosophical theologians, people who did not believe in the use of logic to decipher the meanings of religious texts, according to Khalaji. In such a religious climate, the believer would put more faith in his Shiite imam than in rationalism in order to solve the problems of the world. The place from which Khamenei sprang taught him that rational thought has no legitimate place in the decision-making process, and the superstitious aspect of religion is the one that has the most weight, he writes. According to this mode of thinking, the spiritual leader effectively takes decisions based on his reading of the future, which is predicated on interpretations of random passages from the Koran or prayers that are specially tailored for holy people purportedly connected to the hidden imam. Despite his religious education, Khamenei must concern himself with the stability of the regime by dint of his job title. This obligates him to refrain from threatening war against the West, even if he views this as a legitimate course of action. Ahmadinejad comes from an entirely different background than that of Khamenei. The presidents world is one in which politicians worship religion. It is a world that came into existence with the revolution of 1979. Ahmadinejad belongs to a secretive cult which believes in the imminent return of the hidden imam. This group, which includes the president of Iran, does not offer up much credit to the religious establishment or the religious sages, since it does not consider them as sufficiently armed with the knowledge that would enable them to understand theological texts written in the Arabic language, Khalaji writes. In fact, this group sees itself as the authentic representative of Islamic study whose prophesied mission is to change the face of Iranian society all in preparation for the return of the Mahdi. It is very difficult to know what the members of this very mysterious group really believe, but it is widely thought that these individuals yearn to take control of the Iranian nuclear project, Khalaji writes. There are even those who claim that Gholam Reza Aghazadeh, who until 2009 served as the president of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran and was also the countrys vice president for Atomic Energy, belongs to the same cult as Ahmadinejad. Today, Aghazadeh is a member of the Expediency Discernment Council, an advisory council to the regime. Khalajis conclusions are dramatic. Some members of Ahmadinejads close circle of advisers have engaged in neo-Nazi activities in Germany, he writes. Mohammed-Ali Ramin, the current deputy culture minister for press in Iran, also serves as Ahmadinejads chief adviser on the Holocaust. The agency he leads is tasked with disseminating Holocaust denial in academic circles in order to bring universities closer in line with the regimes thinking on the issue. It seems that the ideology espoused by Ahmadinejads group is one that fuses socialism and Nazism, all within the framework of Islamic fundamentalism. We must come to grips with the fact that a deeply religious fanaticism particularly that of Ahmadinejad - is what drives the current Iranian leadership. Whoever comes into contact with the president gets a first-hand glimpse of his obsessiveness over the coming of the Muslim messiah, the hidden imam. According to Shiite belief, the hidden imam is a mortal who is immune to error. After the Iranian president returned from a visit to New York, during which he reveled in his participation in the U.N. General Assembly, he told his colleagues that during his speech, the hidden imam filled him with a halo of light. Ahmadinejad bragged that during his 30-minute speech, the audience was so riveted that nobody blinked even once. Ahmadinejad believes that aside from employing advanced technology like nuclear weapons, there are other ways to expedite the arrival of the messiah, namely launching a global jihad that would destroy the Great Satan (the United States) and the Little Satan (Israel). He is even convinced that he personally met the Mahdi, or at least that is what he has told his supporters on numerous occasions. Ahmadinejad says that the Mahdi gives him instructions to prepare Iran for apocalyptic war which will result in the destruction of Judeo-Christian civilization. Paradoxically, there is a desire among the religious sages of Qom and Najaf to downplay the return of the hidden imam, since his return would essentially spell the end of the religious establishment, Khalaji writes. This is because the establishment views itself as the representative of the 12th imam during his absence. Khalaji also considers the Revolutionary Guards and its paramilitary volunteer division, the Basij militia, as receptive audiences to the end of days theories. Those closest to the Iranian leadership have succeeded in inculcating the Revolutionary Guards and Basij high commands with the same ideology. There is a simple reason for this. There are two very basic elements that the Iranian leadership must ensure to prepare for the arrival of the hidden imam: an ideologically committed army and nuclear power. Khamenei has the last word on any decisions taken in Iran, but this does not mean that he has exclusivity on all decisions. Indeed, there are other forces at play in the country, some of which limit his influence to some extent. That is why in recent years he successfully worked to weaken some of the other, relatively liberal and democratic elements in the country, particularly those that are considered to be politically moderate. The more Khamenei succeeds in marginalizing these groups, the more he enhances his totalitarian clout, which befits the nature of the Iranian regime today. One must keep in mind the division of powers in contemporary Iran. The president has limited authority, and he has no say in determining the agenda on military matters and economic policy. During his rule, however, Ahmadinejad managed to bolster his position by making populist economic promises as well as by disseminating religious propaganda. Since he was elected in 2005, the president has always tried to boost his influence with the army as well as in nuclear policy. He has not always succeeded in this endeavor, and his popularity in Iran is waning. Even former president Ali Rafsanjani, has become more popular than Ahmadinejad today. Rafsanjani, who served as president from 1989 until 1997, today heads the Expediency Discernment Council, whose main task is to elect a supreme leader when the position is vacated. The Iranian regime exploited the rational image which Rafsanjani presented to the world and instructed its emissaries to repeat moderate messages to the West. Iran made it a point to offer the world a glimpse into the domestic opposition against its president, Ahmadinejad, and to illustrate his limited influence on the nuclear project, all in an effort to divert attention from the apocalyptic ideology that has taken root in Tehran today. If one were to compare Khamenei and Ahmadinejad, Khalaji views the latter as a greater proponent of an ideology that espouses an end to humankind. As the leader and a member of the religious establishment, Khamenei, on the other hand, wishes to maintain stability and prevent the chaos which Ahmadinejad seeks so as to expedite the arrival of the hidden imam. Khameneis task is to preserve the regimes stability, which is against entering into a clash with the West, including the U.S. and Israel. Still, Khamenei, who is chiefly responsible for Irans nuclear program, is a product of the extremist religious seminaries of Mashhad. During recent negotiations with the West over its nuclear program, Saeed Jalili, the Iranian governments point man in the talks, brandished a fatwa issued by Khamenei which bans the use of nuclear weapons. Khalaji finds just cause to doubt the authenticity of this fatwa. Khalaji cites passages from the Quran which command Muslims to arm themselves with the most advanced weaponry in order to face all enemies of Islam. According to Shiite religious authorities in Iran, the killing of women, children, and the elderly is permitted if it is an unavoidable result of destroying an enemy. There is no doubt that nefarious winds are blowing from the higher echelons of the Iranian government, whose rationalism is as hidden from view as the 12th imam.

Behind Iran's push for nuclear power, a hidden deity lurks

In his booklet Apocalyptic Politics: On the Rationality of Iranian Policy, Iranian-American Mehdi Khalaji speaks of a cult working to create a link between socialism, Nazism and fundamentalist Islam.

Load more...