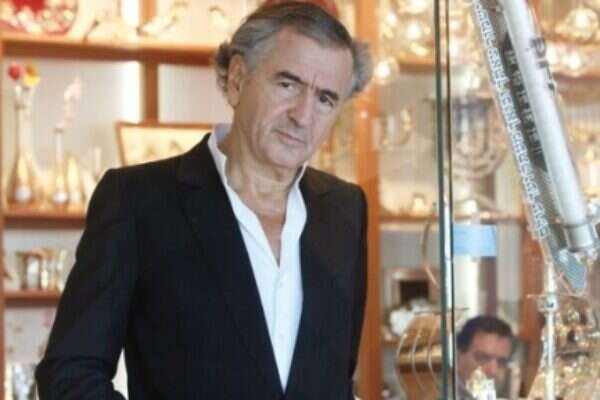

At the end of my conversation with French philosopher Bernard-Henri Levy, I thought to myself that what I heard from him regarding the eternal issues facing our people was far more significant and exhilarating than the political issues that are rehashed ad nauseam in countless other interviews. Levy, a prominent and influential French-Jewish intellectual, philosopher, filmmaker, and author was born in Algiers and lived in Morocco until the age of six, when his family immigrated to France. He was born about six months after the establishment of the State of Israel, and for a long period did not know much about it or his Jewish identity for that matter, save from his biological affiliation. The great Israeli victory in the Six-Day War prompted him to visit Israel at the age of 19. The visit opened a doorway to his Jewish identity. The door opened wider a decade later, after meeting with philosopher Emmanuel Levinas and delving into Jewish learning. Levy was in Israel this month to receive an honorary doctorate from Bar-Ilan University, for more than 40 years of "harnessing his social status, rhetorical skills and contacts hailing from different sectors on behalf of the State of Israel." As an aside, he told me that he was more honored by this title than by others he has received precisely because of the pairings this university embodies "between sacred and profane, between knowledge and study and between science and Torah." This statement turned out to be even more profound than it seemed at first hearing. Bernard-Henri Levy views these issues as part of a long, personal journey reflecting the decisive change taking place within the Jewish world. His book "L'Esprit du Judaisme" (in English, "The Genius of Judaism") was published last year. Q: In your latest book you focus on the figure of the Prophet Jonah who refused his mission, and, after languishing in the belly of a fish, agreed to go to the city of Nineveh and deliver the message God had imparted upon him. Do you see your mission in a similar way- "First of all, I would not call it a mission and I would certainly not compare myself to Jonah. Jonah is the most unexpected, and among the most crucial, prophets in my eyes. He sets a personal example in which he paves a road that I believe is the very beating heart of Judaism. Jonah was caught in a conflict; he was averse to undertaking the mission and initially did not even understand it." Q: Did not understand it? This is an interesting interpretation. "Jonah thought that God was perhaps jesting with him, as He could not ask him to go to the big city of sin, the locus of evil, in order to contribute to its salvation. First, because he thought that Nineveh did not deserve to be saved, and secondly, because it was a great enemy of Israel (as the capital of Assyria). Jonah was conflicted between his love of good and his love of God, and between his loyalty to his people and his desire to obey the divine command." Q: What lesson does God teach him, and us, indirectly- "That being a Jew implies to some extent a relationship with the other, even when the other is the absolute Other." Q: Even if the Other is evil- "No, but when the Other is alterative. Radical evil is another matter. Jonah certainly would not have made a mission to Nazi Germany, nor to al-Qaida or ISIS." Q: Do we have a similar dilemma today? To where do you take Jonah's conflict in our time- "I take Jonah as an example for teaching good. As you know, I made a documentary about the city of Mosul, Nineveh's contemporary name. I was embedded with the Iraqi forces of the Golden Division, which are not among my circle of friends, and I visited Mosul residents who accepted the rule of ISIS, even if to my face were regretful and remorseful about their commitment to ISIS. This was also the situation of the inhabitants of Nineveh at the time. "When I stood in front of those people I wondered whether their remorse was sincere, or whether it was due to the impending defeat of ISIS. I could not tell, but this was precisely Jonah's predicament facing the people of Nineveh." Q: Is it possible that the residents of Mosul admired the ideology or lifestyle imposed on them by ISIS- "In France, those who welcomed the Nazis were well over half the population, perhaps 90%. At first, there was merely a minority of resistance, and only later the ratio was reversed, so you can never know. 'The king's heart is in the hand of the Lord' [Proverbs 21:1], and the heart of the ordinary people -- who knows? I believe that some felt genuine remorse over supporting ISIS. For their sake, the duty of the Western world and of every Jew is to extend a welcoming hand towards them. I cannot always know whether the remorse is sincere, but I must give it a chance." Q: Do you see a parallel between the situation of Nineveh then and between Mosul of today and France of June 1940- "Yes, I see it as a form of Nazism. ISIS is the Nazism of our time." Q: There is a religious background to ISIS. Their appeal is understandable. But what about the French? How did it happen that initially most of the French people identified with the Nazi regime- "Some of those who identified with the Nazi regime were long-standing Fascists. We had in France a fascist tradition since the end of the 19th century; this was old National Socialism. There were many intellectuals and politicians who hoped for the kind of regime that rose in Germany in 1933 and prayed for a similar revolution in France. When the Nazis arrived in France they were overjoyed, as France would now be 'up to date' because it was about to join the Nazi revolution club. "Contrary to them was a resisting minority. But the rest of the population behaved like the people of Mosul: cowards, collaborators -- perhaps due to lack of imagination to envision a rebellion, an alternative possibility, as if they were under the spell of fatalism, unable to do a thing." Q: I recall Marine Le Pen saying a few months ago that France as a nation was not to blame for what happened to the Jews in the Holocaust, as that responsibility belongs to the people who caused the Holocaust. "Her statement was repulsive and untrue. When the Jews were taken, first to the Drancy concentration camp and then to the extermination camps, there were no mass demonstrations and protests of any kind, for a mix of reasons: Some of the French were happy to be rid of the Jews, some of them -- the majority -- were fatalistic about it and therefore did nothing. Thus Marine Le Pen spoke untruth; France did consent to those actions." What is the Meaning of Choice- Q: You write a lot about the term "choice" in the context of the Jewish people. How do you understand it- "The idea of choice appears in the Torah in another context, 'segula,' which refers to a secret treasure. Hence 'am segula,' a treasured nation. The conclusion I reached in my book is that the Jews are the secret treasure of humanity. They are a secret unto themselves -- they seldom know this -- and a secret to others, who also do not know. The fact that they do not know that Jewish thought is their treasure, and the fact that those who embrace Jewish thought do not know that they are a treasure, does not prevent the segula, the virtue, from being what it is. Q: This still does not explain what it means to be chosen. In our people's latest adventure, the secularization process that started in the mid-18th century, one of the tools of secularization was to reject the ideas that the Jews had been chosen from among all the nations. Some saw it as a kind of chauvinism: Why should we feel that we are set apart and different from others- "Though they claimed this, reality proved them wrong. At the time this notion was expressed, the Jews of the Austro-Hungarian Empire were the elite, the 'salt of the earth' of Austrian society. They contributed greatly during the period of remarkable excellence from the mid-19th century until the First World War. In France, along with the rise of secularism, the Jews were a hugely-contributive component of the Republic's culture and of the way of thinking about the social link between the citizens of France. This was the case in pre-1930 Germany, too. So the Jews can say what they like. As I said, there are those who are not aware of them constituting a treasure." Q: Is our contribution to the world an indication of being chosen- "I do not speak of being chosen. Neither does the Torah refer to a people merely being chosen, but rather of an 'am segula' [treasured people]." Q: Why is this? The customary blessing recited before reading from the Torah is "... who chose us from all the nations and gave us His Torah." Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook used to say (following the Maharal of Prague) that the order teaches us about the hierarchy of the process: First God chose us and that is why He gave us the Torah. The choice is not conditional. It is not due to the Torah that we are the Chosen People. "The story is more complex. The people of Israel chose God, at least as much as God chose them. They endorsed the Torah after all other nations declined it. God says that He loves all the nations of the earth and that all are dear to his heart but among them there is one. So this is a more complicated story. It is not merely that the finger of God had ostensibly indicated that 'These are my guys.' It is not a status that permits exclusive tribal pride, chauvinism. "There was one important Jew named Korach who believed in this authorized Jewish chauvinism, and he gathered people around him to go against Moses. You know what happened to him." Q: He protested against Moses on the grounds that "the entire community is holy and God is amongst them, and why should you raise yourselves above the congregation of God-" "Indeed. And his call of the sanctity of the Jewish assemble, there and then, is the greatest of crimes. Moses asks the earth to open its mouth and Korach and his followers are swallowed alive. This is a huge punishment as it is also a new act of creation. So Korach's mistake is one of the cardinal mistakes a Jew could make: to believe that the segula, the treasured status, is an authorized prerogative for national chauvinism. Q: Interestingly, the philosophy of Rabbi Kook senior, Abraham Isaac Kook, sees a connection between Korach and Christianity, in the way they both reduced all classes to a single one -- all of them holy without hierarchy or cause for effort to attain holiness. "Your level depends on the degree of your commitment to the Torah, to Torah study, on your contribution to the degree of holiness among the people. On what does this depend? On the ability to add a drop of ink to the ocean of commentary. Not obedience, not repetition, not constant recitation. A Jew who has devoted himself to adding a drop of ink to the ocean of commentary is on the path of redemption." Q: Do you view your, and others', writing on Jewish thought as part of a very long Jewish tradition of commentary- "There are two Jewish traditions, of equal importance, regarding texts. One is the tradition of commentary. A serious Jew is not content just with orthopraxy [doing the right thing], being correct and right, but is interested in making a point. In my book 'The Testament of God' from about 35 years ago, I tried to clarify a point, a trifle. Today, in my latest book, 'The Genius of Judaism,' I try to add my grain of truth to the body of commentary, for example on the subject of Jonah. I began to study all the existing commentary, which I know quite well, and my aspiration was to add a small something. Did I succeed? That is a question. But this is one of the vocations of a Jewish intellectual. "The second is to connect the study with the knowledge, or the knowledge with the study: to connect and link the two bodies of text, the profane and the holy. This is also a great mission for the Jew, as exemplified in the best Israeli universities: to confront the two bodies of text, science and general literature with sacred studies, the book of books with general books. To imbue the books with a resonance and echo from the book of books, and vice versa. This way, back and forth, between the book of books and the general books, constitutes the true Jewish deed and commitment." Secularization and Orthodoxy Q: In Israel, people often identify the Torah and Jewish culture with political parties and internal Israeli conflict, instead of all the treasures you speak of. "I am aware of that, and that's a pity. The so-called 'dividing line' -- the 'contrast' between 'secular' and 'Orthodox' -- is so unnecessary and absurd. I know that in Israel this contradiction supposedly exists, but it is not real. I am secular, but occasionally, not always, I feel closer to the Orthodox, to those who are called 'religious,' rather than to the 'secular.' I refuse to accept the idea that the religious person, the yeshiva student, is called 'Orthodox.' Who is orthodox? One who mechanically observes the religious act and repeats a text that is frozen in time. A real student who studies in a real yeshiva and devotes his time, his mind, and even his body, to delve deeply into the text of the Torah in order to add of his own to the existing commentary, to add to its complexity and sophistication, is the exact opposite of orthodoxy." Q: Judaism is dynamic, alive. "What annoys me is that many of the so-called 'Orthodox' are actually the opposite. They fight against Orthodoxy, that is, they fight against the frozen text. So the new war of the 'secular' Jews is the very example of an artificial conflict. My goals are to build a bridge between the two and not to perpetuate the contrast. In Israel, it is this narrative which must be nurtured and returned to the best of Jewish tradition." Q: Do you know that if you enter any place of Torah study, even if you do not understand the content of the words, but only listen to the verbs used, you will notice that the language does not refer to the past -- as in, "Rabbi Akiva said," "Rashi mentioned" but rather the present tense. The Jews' texts do not belong to the past, they don't belong in a museum. Rather, they surround us here and now and we engage in constant dialogue with them. "Of course. A Jew reads every verse of the Torah as if it had 70 faces, or facets. The number 70 is significant, as it refers also to all peoples -- the seventy nations of the world -- but the meaning of the 'faces' here is that you can look at them, make them smile and light up their eyes. This is an incredible notion, so strange and profound, to say that a verse has a face. It means that it has a presence here and now." Q: You are actually telling the secular public that it is missing something by not embracing all this treasure. "I do think they are missing something if they stop perpetuating the spark between this treasure and the other treasures. The books of Stephen Zweig, Hermann Broch, Joseph Roth, and Philip Roth, for example, are treasures, but so are the commentaries of Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin, the Vilna Gaon, or Rabbi Nachman of Breslov. One of the greatest things a Jew can do is to connect between the two treasures. Anyone who does not do so is lacking, of course. The Process of Return -- Sartre and Levinas Q: How did you connect to this part of your identity- "I came to it in my late twenties, after having published my first books, upon meeting Emmanuel Levinas. That was the moment of my teshuva, my 'repentance,' the moment when I was caught by a word, a language that I did not know, that I did not speak, that I still do not speak. That is what led me to write the 'Testament of God.' Q: Up until then you were a student of the philosopher Jean Paul Sartre together with Alain Finkielkraut and Benny Levy, and you all made a turn when you met Levinas. What did you find in him- "Levinas unveiled for me an entire world which I had ignored, a world which made me advance and makes me continue thinking for the rest of my life." Q: Why did you ignore that world until then- "Because my family had taught me to do so. My family was extremely secular. Like many Jewish families in Europe, my family also emerged from the Second World War with the notion that the page had to be turned." Q: Because the price we paid for being Jews was too heavy- "Yes. That was my father's conviction. He was a fighter, a hero of the struggle against the Nazis. He was angry with the Nazis, of course, but he thought, mistakenly, that to be a Jew was an unbearable burden." Q: So he supported assimilation- "Yes, total assimilation. Until I was about 30 years old, I never opened a Jewish book, not even a Bible, and I did not visit a synagogue. I knew I was a Jew but I did not know what that meant." Q: Did Levinas help you reconcile between the world and your identity- "Not just reconcile. Levinas was a guide. He showed me several books, first of all his own, his Talmudic readings, which I devoured. He made me realize that if I wanted to move forward, I had to encounter that part of my identity -- a term that I do not like to use -- that part of my world." Q: Why don't you like the term identity- "Because, as I said earlier, in relation to Jonah, for me to be a Jew is less a matter of identity and more a matter of alterity -- otherness. Through Jewish thought it is possible to cause the thawing, breaking down, sophistication of identities, and therefore talking about identity always leads to reduction. That is why I would rather speak of being a Jew. I am a Jew." Q: Was Levinas trying to translate these treasures into intellectual language as a response to intellectuals who came out against Judaism? Is that what you try to do too? "Exactly. I try to do in a modest way what Levinas did spectacularly." Q: So it is a question of language- "No. It is a question of translation, not from one language to another, but a symbolic translation into another world. Levinas' project was to translate Hebrew into Greek, figuratively, symbolically. But also to translate Greek into Hebrew. There were both these ways in Levinas, and I tried to be faithful to both twin gestures." Q: You knew Sartre and Levinas very well. What is the difference between them- "Everything. Sartre was the pillar of secularism and atheism, with no doubt about them. His entire life had been devoted to deepening, embracing and asserting the atheistic view of the world. At the end of his life something amazing and strange happened. He encountered Levinas -- more precisely his books -- via Benny Levy, and this discovery of Levinas shook the foundations of Sartre's life." Q: When did this occur- "In his last years, until his death in 1980. During these years, Benny Levy and myself would meet with Levinas. However, we were barely acquainted with each other. Sometimes Levinas would receive both of us on the same day. For Benny Levy this contributed to his writing, but also to what he conveyed to Sartre, as he was his secretary. He introduced to Sartre the gold mine he had received from Levinas. At this stage of his life, Sartre was blind and Benny would read to him and serve as his eyes. And so Benny read to him the books of Levinas which he was in the process of discovering. "As a result, Sartre said: For the first time in my intellectual life, I see clearly what I lacked in my work; Because for 50 years what I lacked in my historical research was the concept of messianism; what I lacked in my research on ethics was Jewish ethics; and what I lacked in my social research was the sense of fracture of the community that appears in Jewish thought, and so on. "Sartre continued that awareness of Jewish thought allowed him a new way of thinking which was priceless. He said he was going to start over due to of the new sparks he was producing by confronting the texts of Levinas with those of [Friedrich] Hegel and the text of the Talmud he had discovered. And so, at the end of his life, Sartre began a new chapter in his work and dictated to Levy his last book, 'Hope Now: The 1980 Interviews,' which brings this amazing story. "This story is unknown in Israel, and even in France it is not well-known due to the scandal it caused. The French intelligentsia was scandalized to see its icon -- the epitome of the French intellectual -- say that what he had lacked since his youth was Jewish thought. At the last moment of his life, despite his blindness, Sartre was illuminated -- through Benny Levy -- by the light of Jewish thought. Everyone in France knows this story, even if they do not choose to remember it. At the time it happened, Sartre was said to be senile, but the truth was that this constituted part of his intellectual adventure, perhaps the culmination of his work. I devoted part of my book 'Le siecle de Sartre' (in English, 'Sartre: The Philosopher of the Twentieth Century') to this story of the matching of France and Jewish thought." Hegel and the Silencing of the Jewish Spirit Q: Indeed, an amazing story. What to your understanding was Sartre lacking- "What Sartre discovered was the phantom of the Jewish spirit that has always held Western thinking, but was rejected and censored, especially since Hegel. Hegel triggered the greatest attempt ever to silence and suppress the phantom of the Jewish spirit." Q: Because Hegel saw the danger that Jewish thought posed to his philosophy- "Exactly. One of the cornerstones of Hegelian philosophy was that the destiny of every nation must be embodied in a nation-state. This is because the history of the world is the history of nation-states, and you cannot be a people if you are not a nation-state." Q: And the Jewish existence that Hegel saw in Europe did not fit his formula. "Indeed. Hegel saw two solutions to this problem: Either his format was correct and the Jews would have to disappear, or the Jews would remain and the formula was wrong. Hegel preferred to see his format as correct, and the Jews as a people and an idea were on the verge of disappearance. The first step to their disappearance was to cast darkness upon them. Hegel dimmed and obscured the presence of Jewish thought. From Hegel dates the reputation of Jewish books as outdated, dusty and useless." Q: He also influenced Jewish intellectuals who were ashamed of reading the texts by their own people- "Of course. This is the story of Franz Rosenzweig. When Franz Rosenzweig enters a synagogue for the first time in his life, the day before he planned to convert to Christianity, he does so because he is an absolute Hegelian who believes that Judaism is dead and has nothing to say to the world." Q: This is reminiscent of historian Arnold Toynbee's definition of the Jewish people as a "fossilized relic." "Judaism as a fossil is a Hegelian thought. Prior to Hegel, even in the darkest era of Jewish life, some dialogue was held between Jewish and general thought." Q: But we know that even after Hegel, religious debates were held between Christians and Jews in 19th-century Germany. "But lessening over time." Q: Are you linking the silencing of these treasures to the tragedy that befell our people in Germany one hundred years later- "Yes. Firstly, as I said, the Jews in modern times had become phantoms (figures of the imagination). To be phantoms meant that the Jewish people had perished, or should have perished long ago." Q: But this fate did not start with Hegel. Since the days of Jesus the Jews have been perceived in world culture as the eternal wanderer, Ahasver, whose fate was to wander to and fro aimlessly between the worlds without finding a place of rest. "Yes, but in the last anti-Semitic period, exterminationist anti-Semitism went further. It was not only to condemn our fate to be the eternal wanderer, but to sentence our very existence. At first denying our spiritual existence, our ideological existence, and continuing with the denial of our physical, corporeal existence. There is a continuum. When Western culture took upon itself to forget and silence the text, the Jews became disarmed and immensely weakened. This is one of the explanations why, when the worst arrived, so many Jews did not see it coming, did not expect it, did not recognize it for what it was and therefore did not respond. Although some reacted bravely, but often too late. They underwent some kind of moral and intellectual disintegration which started in self-hatred with the acceptance of the general contempt for [the Jewish] books." Q: That is, they did not accept themselves. They saw these books as the enemy of their own intellectual experience. "These books had become the pillars of our being. These pillars -- even the most secular books of our nation, even those by Jews who do not identify with Israel -- have made us a standard in the world." The Book[s] and Life Q: Nevertheless, there is a difference between books and life. The establishment of the State of Israel can be seen as a revival of the book and of what it recounts. The Jews have reverted from phantom status to that of a living nation in its homeland. How does the State of Israel affect European, religious and secular thought- "In the early days of the State of Israel, it was proven to the world and the Jews that the pillar still stands, that Jewish thought is still alive. It reminded those who were in doubt that Judaism was alive." Q: But why do we need a state? Why can't we live only in books- "That is indeed the question. It is true that the founding of the State of Israel credited Hegel in a way, to say that we also are a people with a state, and indeed there is a Hegelian aspect to Zionism." Q: But we were a nation that had a kingdom thousands of years before Hegel. "Exactly. And the great wisdom of the Jews in the last 70 years was to continue to support, nurture and nourish the State of Israel on the one hand, but also Jewish values regardless of the State of Israel. That was the great wisdom of our generation, [David] Ben-Gurion and Levinas, Gershom Scholem and Franz Rosenzweig. There was a great debate between Scholem and Rosenzweig in the 1920s, with Scholem immigrate to Israel and Rosenzweig remaining in Germany. Ultimately, Scholem helped establish the Hebrew University, and Rosenzweig wrote 'The Star of Redemption' in exile. Even today, the Jewish people continue to flourish in both forms, as an independent state and in spreading Jewish values throughout the world." Why do Jews not immigrate to Israel- Q: As a Jew who does not live in Israel on a regular basis, what is Zionism for you- "To support Israel. After all, there are Jews who do not support Israel. I am a Jew who supports Israel unconditionally." Q: But Zionism means the return of Jews not only to history but also to their homeland. I understand that 70 years ago, before 1948, there was a possibility to live both in the Land of Israel and in the Diaspora, and Jews lived both here and there. But after we established an independent state, why didn't all the Jews come to Israel? Isn't it time to leave behind two thousand years of exile and return home- "I believe that the Jews have two different missions: to build a homeland on one hand and to create a dialogue with the 70 nations on the other." Q: Can't we converse with the 70 nations from our country? The Prophet Isiah spoke from Jerusalem to the whole world as early as the eighth century BCE. "Yes. I know that. And that is of course the main question. Perhaps one day I will think that the best way to fulfill the Jewish mission is to address the world from Israel. Sometimes I think and believe so. Not just once a year; even a few times a day do I have this thought." Q: What is the current state of French Jewry? Is it the same as it was 50 years ago- "There is a new form of anti-Semitism. A new version, based mainly on anti-Zionism. Because it is a new form of anti-Semitism, it is not identified as such by a large number of opinion leaders in France, which is why it is all the stronger. However, the French Republic and its elite still show strong opposition to this anti-Semitism." Q: Why are you struggling to remain in France with all its problems? I think of Ezra and Nehemiah, intellectuals who led their people around the fifth century BCE to leave the Diaspora and return to the land of Israel. You too can tell the Jews to return home with you. "I still think that the Jews have a role, not only in dealing with the 70 nations, but also in living among them. Jewish thought also has a redeeming role to play in this aspect. I may change my mind. But know that for me, I am in the dark on this subject. I am not certain of what to say. The fact is that I do not live in Israel and did not immigrate here. This was a subject for debate between me and Benny Levy. I continue to live my Jewish life by trying to spread the Jewish spark in France. Will I continue doing so for the rest of my life? I cannot say."

'Jews are the secret treasure of humanity'

Being recognized for his contribution to Israel is more flattering to Bernard-Henri Levy than many of the other honors of his career • Today, the Jewish-French intellectual, who didn't set foot in a synagogue until he was 30, remembers where he came from.

Load more...