Sixty-six years after the end of the Second World War, we are still uncovering new, fascinating stories and subplots about the most traumatic period in the history of the Jewish people. Many of these revelations deal with stories of rescue and heroism that were never told before. The only ones who know of them are the survivors themselves as well as the descendants of the rescuers. The Tunisian rescuer, Khaled Abdul-Wahab, is one of these lost stories. In recent years, he has earned the moniker the Arab Oskar Schindler. Nonetheless, he has yet to earn recognition as one of Yad Vashems Righteous Among the Nations. Khaled was born in 1911 to a family that was well-connected both politically and culturally. His father was a culture minister in the Tunisian government as well as a kadi (a judge in an Islamic court). The Abdul-Wahab family was quite wealthy. They lived on a farm near the town of El Djem, which is not far from the coastal city of Mahdia, an area that boasts a Jewish community. Khaled grew up to cut an impressive figure, with noble looks and a modest character to boot. In his 30s, he spent a few years in New York, where he worked as a model photographer and learned architecture, art history, and archeology. On one hand, he was a cosmopolitan through and through. Yet he was also a man who was deeply rooted in his Tunisian identity while maintaining loyalty to his family and friends back home. This explains why just before the outbreak of the Second World War, he returned to Tunisia. While the Vichy government that ruled Morocco and Algeria heeded the German directive to build dozens of concentration camps; and while Italian-ruled Libya collaborated with Hitler, the situation in Tunisia was different. Contrary to her neighbors, Tunisia came under direct Nazi rule in 1942. The Germans built concentration camps, and in the spring of 1943, when the German campaign of the persecution of Tunisian Jewry reached a fever pitch, many tried to escape. Approximately 5,000 Jews from Tunisia were sent to labor camps, while a few of them were transported to extermination camps. Hundreds died either from starvation, death marches, or illness. The Tunisians were largely indifferent to the German purge of their Jewish compatriots, but Khaled Abdul-Wahab was exceptional. Research that was done after the war revealed that during the Nazi occupation, Abdul-Wahab sheltered two Jewish families the Boukhris family and the Uzzan family that numbered dozens of people. He hid them on his farm during the Nazi effort to track down the Jews. What makes the story even more remarkable is that Khaled hosted a group of Nazi officers on his farm so as to gauge their future plans. When the Boukhris family was expelled from its home, it subsequently hid out in a textile factory. From his conversations with the Nazi officers, Khaled understood that a manhunt was ongoing in search of Odette Boukhris, the family matriarch. That night, Khaled rushed over to the textile factory to bring the family to his farm, where they could hide for an extended period. Two years ago, Edmee Masliach, a member of the Uzzan family who was living in Paris, returned to Tunisia to pay a visit to Abdul-Wahabs farm. She was 11 years old at the time, but her memory of the old building in which she hid 60 years prior was crystal clear. One night, a drunk German soldier who was at the farm discovered the concealed families, she said. He talked to us for two hours, and he said: I know that you are Jews and I am going to murder you. It was at that moment that Khaled came by, as if he was the Messiah. He managed to throw the German out and to take his weapon. An 11-country search Khaled Abdul-Wahab was still a shy man after the war. He did not brag about his actions, and he confided in just a few of his relatives as to what happened in the 1930s. His modesty may have also led him to oblivion, for he was never recognized as a Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem, this despite the fact that a number of Jewish organizations in the U.S. have posthumously bestowed various honors upon him. Still, his name has gone largely unmentioned for years, until Robert Satloff entered the picture. Satloff, a writer, historian, and Jewish-American researcher, got a firsthand glimpse of the September 11 terrorist attack. The horrors of that day reminded him of images from the Holocaust. He said that he was appalled by the disconnect that the attacks created between Muslim and Western societies. This motivated him to research Arab attitudes toward the Holocaust in the hope of finding a bridge that would link the two peoples. In his research, Satloff reached contradictory findings. On one hand, Holocaust denial has become an acceptable phenomenon in Arab society. On the other hand, many have recognized the Holocaust in order to use it as a reference point in comparing that tragedy to disasters that have befallen other nations, including the Palestinians. That was when Satloff came up with a far-reaching idea: to dig up information about Arabs who rescued Jews during the Holocaust. Satloff took on this mission in concert with his wife, Jennie Litvack, an economist at the World Bank. Jennie was dispatched to Morocco along with a special team of researchers which was disbanded and dispersed to 11 different Arab countries, all in an effort to track down righteous gentiles. The research took four years, and in 2006, Satloff published his findings in a book titled, "Among the Righteous: Lost Stories from the Holocausts Long Reach Into Arab Lands." In the book, Satloff recalls meeting Annie Boukhris, a Jewish resident of California who is of Moroccan descent. During the meeting, which took place a short time before Boukhris death, the author learned of a landowner who hid her family on his farm during the Nazi liquidation, in the process saving the lives of another Jewish family. It turns out that the landowner was Khaled Abdul-Wahab. After the books publication, producer Karen Davison and director Bill Cran released a documentary film titled Among the Righteous: Lost Stories from the Holocaust in Arab Lands, which is now being screened at the Jewish Eye Film Festival in Ashkelon. The documentary is expected to air soon on Channel 2. Meeting the survivors Faiza Abdul-Wahab, Khaleds daughter, lives in Paris. In an interview with Israel Hayom, she reminisces about her father. He was a shy, introverted, and discrete man who spoke little, she said. He never spoke of the fact that he rescued Jews. One day, I came back from school after having learned about the Second World War. I asked him where he was during the war. He answered: I was in Tunisia. I asked him what happened to the Jews. He said, I had a few families on the farm. He did not go into details as to how many people he saved and who they were. After the war, Abdul-Wahab remained in Tunisia, though he did make frequent trips to Paris and Madrid, where he met his actress wife. It was only when she read Satloffs book that Faiza learned the full extent of her fathers heroism, a full nine years after his death at the age of 86. She recalled how amazed she was to discover what he had done, and how it compelled her to quickly make contact with members of the Boukhris and Uzzan families, who were hidden on the farm. In California, I met Ania, Annie Boukhris daughter, she said. I did not even have time to be proud of what my father did, because within seconds we became friends. It reminded me that Tunisia is such a small country. Before the war, people were together. Jews and Muslims shared everything. A magnanimous man Edmee Masliach (Uzzan), the girl who hid on the farm, met Faiza when both were on an airplane en route to the filming of the documentary. Here, too, Faiza hit it off immediately with Edmee. Edmee invited me to her birthday party and her daughters bat mitzvah, and I am also invited to her Shabbat dinners and other events. These people are like my new family. Aside from them, I have no other family. The book and the film have brought Abdul Wahabs heroism to light. Faiza was subsequently invited to receive numerous awards in her fathers name from Jewish communities the world over. The year in which the book came out, 2006, was a very impressive, respectable year, she said. I was invited to the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, Yeshiva University in New York, the Adas Israel Synagogue in Washington, DC, the Holocaust Museum, and many other events. Everyone wanted to remember and to pay homage to my fathers memory. I met many warm and good people. It was wonderful. The film states that honoring Abdul Wahab is tantamount to a tribute to the other unknown Arabs who saved Jews. Still, he has never earned official recognition from Yad Vashem as a Righteous Among the Nations. Why? A person who is classified as a Righteous Among the Nations is someone who risked his life, said Irena Steinfeldt, the director of the Righteous Among the Nations Department of Yad Vashem. In other words, not only did that person save Jews, but he put his life on the line by saving them. That is the criterion that distinguishes a righteous gentile from other people who helped and showed solidarity. This is meant to differentiate between people who were ready to pay a heavy, personal price to rescue Jews and those who did it firmly in the knowledge that nothing would happen to them as a result. All of the Jews of Mahdia were evacuated, Steinfeldt said. The Uzzan and Boukhris families stayed with Abdul Wahab, and there other Jews who stayed on another farm that belonged to a local man named Bukovza. The men went to do forced labor and returned to the farm at the end of the day, because at this stage the Germans had not yet begun deporting Jews. One witness said, The Germans would occasionally come by [the farm] and count us. In other words, her statements suggest that the Germans knew that the Jews were staying with Abdul Wahab. While the Jews did live there under difficult conditions and in dilapidated buildings, the Germans knew they were there, she said. Abdul Wahab hosted them and did a very noble thing, and I presume that he helped them get by. We have here a case of a magnanimous man, but fortunately for everyone, there was not a situation in which he had to put himself at risk by hiding them. In essence, he hosted them more than he hid them. Steinfeldt conducted her own research into the events which unfolded in Mahdia shortly after Satloffs book was published. She buttressed her arguments by citing testimonies that she heard during her work. Annie Boukhris, who had hidden on Abdul Wahabs farm, described how they would often visit other Jewish families to prepare for Shabbat, she said. I listened to Annies testimony very carefully to make sure that we were not mistaken. The people that I talked to told me that they would go to the military hospital whenever they needed medicine. They came out from their hiding place. Edmee did not describe to me a traumatic period of her life when she feared for her safety, but because she was just 11 years old, it is impossible to rely on her feelings completely. What is clear is that the wealthy Jewish families were forced to live in conditions that were unpleasant. Steinfeldt added that she was in touch with German researchers who studied the period of Nazi rule in Tunisia. I checked the German army archives about a military encampment that was said to be in the area of the farm, she said. It turns out that there was a German command post in Mahdia, but the SS task force, whose job was to deal with the local Jews, was not stationed there. Look, I have nothing against the book or the film, she said. Abdul Wahabs actions are worthy of mention, but they do not meet the strict standards for recognition as a Righteous Among the Nations. A political game Faiza, Abdul Wahabs daughter, acknowledges that she does not know the true extent of the danger in which her father acted. Yad Vashem says that my father did not take any risk, she said. I just know that he did what he wanted to do and what he thought needed to be done. He was always independent and free-thinking, and he did not think about the danger, but rather about the people. These Jews were Tunisians, his friends. He worked with some of them, and he developed friendships with them. My father acted out of instinct. Unlike Faiza, the films director expressed amazement at Yad Vashems decision. In my view, it is strange that Abdul Wahab was not included on the list, said Bill Cran. Obviously he put himself at risk when he hid Jews in his shelter. Luckily, he was not killed or arrested, but it is a fact that he took weapons from the Germans when he hosted them. The families that he hid claim that he was in great danger. There are stories of other Tunisians who hid Jews and suffered. At that time, senior Nazi officers were in the country, so the risk of hiding Jews was clear. I feel that this discussion, about the first Arab becoming a Righteous Among the Nations, has turned into a political game, Cran said. The Yad Vashem board wants to prove that they are not wrong, and they are clinging to whatever they can so that [Abdul Wahab] will not be there. I think that justice needs to be done with the memory and the commemoration of Abdul Wahab. Yad Vashem has high standards of proof and I appreciate and salute them, but still, we also tried to be careful and skeptical about the story, until Edmee came and volunteered the information to us about what happened and how Abdul Wahab saved them. Cran is not the only one who has criticized Yad Vashems decision. Reached at his home in New York, Satloff touches on a number of points. Even within Yad Vashem there is a huge argument about this, he said. Irenas predecessor, Mordechai Paldiel, as director of the Righteous Among the Nations Departments wrote an op-ed in The Jerusalem Post in which he said that Khaled was deserving of being named a Righteous Among the Nations, and he explained why. Satloff does not see eye to eye with Yad Vashem. Defining a righteous gentile as someone who risked his life is something that did not exist for many years, he said. What about the diplomats who saved Jews? The American diplomats, Japanese, and even Raoul Wallenberg. Nothing ever happened to these diplomats because they were protected, so how are they considered Righteous Among the Nations- Everyone is an expert regarding the dominant topic of the Holocaust of European Jewry, which is obviously the central story of the Holocaust, he said. But I am afraid that none of the members of the Yad Vashem board is well-versed as to what happened in Tunisia. Yad Vashem took three testimonies from women who were rescued by Abdul Wahab. As someone who has followed the story for years, I can say explicitly: their lives were saved thanks to the person who saved them. Witness accounts clearly contradict the claims made by Steinfeldt and Yad Vashem. The women claimed that the Germans came to their hiding place and threatened their lives, but Khaled came to their defense and saved their lives. It is true that there were certain Germans who knew that they were there, but the relevant fact is that those same Germans endangered [the womens] lives and Khaled protected them. Soon it will be five years to the day that Khaled Abdul Wahabs name was submitted for consideration as a Righteous Among the Nations. He was rejected by the board. Afterward, his name came up again as a candidate, and he was once again rejected. Two rebuffs is a rare occurrence. I have a great deal of respect and admiration for Yad Vashem, but in this case common sense has been pushed aside, Satloff said. When you go to Yad Vashem and visit the Valley of the Communities, you can see a stone with the names of cities in Tunisia, including Mahdia. If they recognize the fact that the Holocaust had reached all the way there, then at the very least you should recognize the possibility that Jews were rescued there.

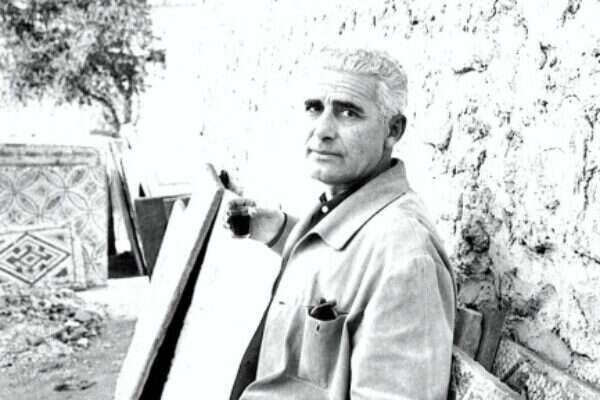

The righteous gentile youve never heard of

Khaled Abdul-Wahab was a wealthy Tunisian who hid several Jewish families during the Second World War, saving their lives. A new documentary investigates his story as well as the opportunity missed by Yad Vashem.

Load more...