When the Yom Kippur War went into its third week, the enemy was already hard hit. Troops from the elite IDF Sayeret Matkal reconaissance unit were approaching the Egyptian city of Ismailia, west of the Suez Canal. Pillars of smoke rose high, evidence that the bridges over the canal had been destroyed. Although the Egyptians had not yet fled, their troops had pulled out, making our northward advance more difficult. The division commander, Ariel Sharon, was undaunted. He immediately issued an order, mixed with his typical bite, saying: "Muki's guys [referring to Muki Betser, the unit commander] can swim if they have to." And so it was. The troops, experienced in military operations at the Suez Canal, crossed it as if they were swimming in a children's pool. Two hundred meters of calm water, not even faintly reminiscent of the tough (and only) obstacle that the unit had faced until the Six-Day War -- the Jordan River. While it was narrower than the Suez Canal, during the winter the Jordan's flow was strong and dangerous, and during some military operations it had claimed lives. Back to the Suez Canal, which our troops crossed many times to prepare for the next war, the one we hoped would never erupt. Nov. 8, 1972, nighttime. Naval commando troops Baruch Fratzman and Akiva Shahar, with whom we had trained for several weeks, were ready in their wetsuits, gliding along the bank of the canal. They moved quickly, pulling the rope that was needed for the operation across the canal, beneath the water's surface. They were silent and invisible until they sent the agreed signal over the radio, indicating that the commandos could be sent over to penetrate Egyptian territory. Ehud Barak, who was the unit commander at the time, and his deputy, Yoni Netanyahu, gave the green light to our commander, Itamar Sela, to begin crossing. There was no resemblance whatsoever between the canal we encountered a year later during the Yom Kippur War and what we encountered that night. *** The way we lay in ambush west of the canal on the night of Oct. 22, 1973, as tracer bullets (fired in celebration of the cease-fire that was supposed to go into effect at midnight) was replaced by utter gloom as we entered the freezing water. For the first time I understood the meaning of the phrase "the darkness of Egypt." The silence was absolute also, until the sound of the rappelling ring that connected each combat soldier to the rope that Fratzman and Shahar had prepared for us split it like a shot from a Kalashnikov rifle. Since we could not train for the operation in the Suez Canal itself, we trained for it in the fishponds of Kibbutz Maagan Michael, where Yoni Netanyahu lived. We crossed the length and breadth of the fishpond and went across diagonally too so as to become accustomed to the actual distance involved in crossing the Suez Canal. But there were two key differences. First, there were the fish in the kibbutz pond. They showed a great deal of fondness for the exposed parts of our bodies, and bit the combat soldiers' shins over and over. The second was the kibbutz environment. The lights and the noise of cars gave no hint of what the Suez Canal was really like at night -- dark and silent. Yoav Margalit and I were tasked with removing mines. We trained one night on the kibbutz, at the behest of Yoni Netanyahu. Like everyone, he was very much afraid of the mines planted between the canal bank and the road on the Egyptian side. I do not remember the search, but I will never forget the taste of the Shabbat challah bread that Yoni brought us out in the field when we finished. We had gone out to search for mines and found challah. Meeting up with Fratzman and Shahar on the Egyptian side of the canal a moment after we finished crossing the freezing water was like meeting relatives after years apart. Margalit and I took off our wetsuits, put on our bomb-disposal suits and started poking Egypt's soil to mark out the safe passage to the Egyptian road with white ribbons. In the field, with the darkness of Egypt all around us, the two white ribbons became spotlights that could be seen from a distance, even from the Israeli side. We hurried to take the equipment, of which there was a great deal, out of the sealed bags, and all the troops passed in front of two members of the navy commando unit, who remained at the end of the path on the bank of the canal. The walk among the reed stalks was brief -- and moving each stalk aside was like cracking a whip on a mule. Omri Padan and Shauli Baram, two combat soldiers from the team whose task it was to warn of enemy movement on the road, remained at the edge of the path beside the road. The rest of the team, joined by another member of the naval commando, Ron (Berele) Ber, continued at a quick pace into the dark, open space, deep inside Egyptian territory. We reached the lookout point at the appointed time. We were alert for any sound and scanned the area with night-vision equipment, everything familiar to us from the material we had studied for the operation. Nothing was heard for hours but whispers over the two-way radio. The stars above us were the only points of light. At 2 a.m. we were to pack up and go back to our area before the dawn began to break. *** A year later, when the break of dawn showed the Egyptians that the Israeli army was on the outskirts of Ismailia, the cease-fire collapsed. We were lying flat in the water-collection plates around trees in an orchard, near the path, when we came under heavy fire. The bullets whistling among the trees forced us to stay as close to the ground as we could. Dozens of RPG rockets split the air. From time to time, they hit a tree branch. That's better than us getting hit, I thought to myself. We paid a hefty price for our position at the edge of the orchard. Amit Ben Horin, who commanded part of the force, was going from one position to the next, giving out firing patterns. After instructing us, he stood up to instruct the commander of the adjacent team, and an Egyptian bullet struck him in the head. He was killed instantly. About 20 soldiers of the unit were wounded in that incident, including Itamar Sela, our team's commander from the day we had enlisted. Since then, I have learned that cease-fires must be treated with respect and suspicion. The Yom Kippur War ended after another day of fighting. The casualties of the last battle on the last day are always the toughest losses of all. *** A year earlier. Itamar Sela was showing us how to organize the equipment prior to packing up. In the dozens of operations in which I took part, this was the happiest moment. It was like the long-distance runs in which you pass the halfway mark and start returning to the starting point, knowing that from now on every meter you run is bringing you closer to home. It is like that in a military operation. Suddenly there is a feeling of exaltation as adrenaline pumps into every limb of your exhausted body. But then came the terrible explosion in the dark, silent space of Egypt, sounding like a shell fired from a tank. Although we had trained for many possible scenarios, none of them included such a deafening blast. A quick check over the two-way radio indicated that something had happened to the troops on the bank of the canal. We went from a walk to a run, trying to pick up Padan and Baram. We found Shahar on the bank of the canal. He had been wounded after rescuing Fratzman from the water, where the shockwave of the explosion had propelled them. Margalit, who also functioned as a medic, ran to apply a tourniquet to the stump of Fratzman's left arm, which had been blown off in the blast. Bereleh hurried to inflate a small rescue raft on which Fratzman lay as we made our way to the rescue boat that had infiltrated from the Israeli side. The courageous and handsome Fratzman had been saved again, but he was very badly wounded. Other parts of his body, including his face, had been hit. He was evacuated to Soroka Medical Center in Beersheba, where it took weeks of agony for doctors to stabilize him. Months of rehabilitation passed before he could stand on his feet once again. Fratzman's strength served him during his journey to recovery, and eventually he returned to the sea to become Israel's sailing champion. In due course he became a grandfather, and could tell his stories to his grandchildren. What was the origin of the explosion that sent everyone flying? It turned out to be an anti-personnel mine that the Egyptians had planted along the bank of the canal. While Fratzman and Shahar were waiting for the troops to return, a noise startled them, and as they had practiced during the training drills, they hurried to remove the white ribbons. When they did not spot anything suspicious on the ground, they went to replace the ribbons on the road -- and that was when Fratzman rested his elbow on the mine. * * * After Fratzman and Shahar were taken to hospital, tension increased among the combat soldiers and the command post: What had resulted from the noise of the explosion? What did the Egyptians gather from it, and had they noticed us going back across the canal to the Israeli side? Experience from similar instances in the past calmed no one (in a similar situation in the past, in which a combat soldier of Sayeret Matkal named Benjamin Netanyahu had been involved, the troops, who came under heavy Egyptian fire and suffered severe losses, were rescued with great difficulty). Sela did not wait long to send the team's fighters to the water. Each man attached himself to the rope that the two wounded commandos had stretched across the canal and began to swim for home. A few meters in, Baram whispered to me that one of his flippers had come off. With the amount of equipment that each one was carrying, it was no simple matter to swim with one flipper. We derived a small comfort from the main rope that served us as an anchor and kept us from being swept southward. Unlike the fishpond on Kibbutz Maagan Michael, the Suez Canal had a current that was light but still made things difficult. Sometimes hanging on a rope is a good thing. After going halfway rapidly despite the darkness, we felt that we were finally reaching the bank on our side. But the mission was not over yet. The officers in the command room realized that if the Egyptians were to find Fratzman's blown-off arm (which we had not collected during the rescue) with the diving watch still on it, they would gain an advantage that could prove ruinous to our troops' future plans. Barak quickly told one of the commanders to detach himself from the main rope to return to the place near the bank on the Egyptian side to search for the arm near the water line. But then we had an unpleasant surprise. The commander's rappelling ring refused to open. He tried to cut his personal rope from it so that he could perform the mission, but the main rope was cut by mistake. The search in the dark turned up nothing, Fratzman's arm remained on the ground, but now, without the anchoring rope, all the unit's troops had to fight against the light southward current to get back to the Israeli side. The troops quickly scattered in all directions. Chaos, together with the sounds of the flippers striking the water. The goal was to get back to the Israeli side, as close as possible to the original point. The reason for that had been made clear in the briefing, in which it had been emphasized that the Israeli side was strewn with mines. Getting back there would not be like reaching safe harbor unless we reached the agreed point. Yoni Netanyahu took the responsibility upon himself. He hurried down the path through the minefield and personally led each soldier to the starting point. I met him when I reached the shore. When I asked him whether Baram had gotten there yet, he said no. Baram had been in front of me on the main rope, and the fact that he had not arrived yet was very worrisome. Baram had been carrying a heavy load, like all of us, but with only one flipper. I left my heavy backpacks on the bank and went back to look for him. The noise of a single flipper in the water led me in his direction. I knew his breathing well. We had been in the same tent and the same room since we had started out in the unit. In the air, as well as in the water, he always jumped in before I did. And then I saw him, his nose above water and his mouth under it. He was breathing, but could not make a sound. I took a backpack from him and that was how we got back to the shore. We had made it home. * * * There are many "almosts" in fighting, and those who fought in the Yom Kippur War experienced quite a few. The thousands of casualties, those who fell and those who were wounded, took the hit instead of us. The thoughts of "almost" never let up. The bullet that passed above your head and killed someone else. The helicopter that came to rescue the team from an operation that went wrong deep inside Egypt and was almost left in the field. Here, too, the mine that seriously wounded Fratzman, and you don't know how many centimeters away from it you were as you proceeded deep into Egyptian territory. The cliche says that while we left the Suez Canal, the canal never left us. But the peace treaty that Menachem Begin signed with Egypt did that in the end. Remaining are stories of deep friendship and camaraderie that were bought with blood and sweat -- and a very great deal of each. Avi Dichter is a former Shin Bet director and former internal security and homefront defense minister.

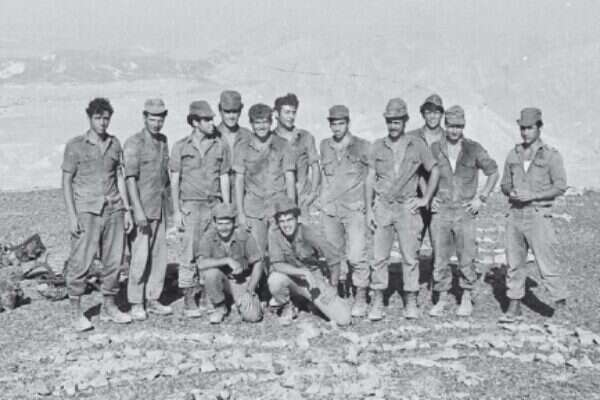

Crossing the Suez Canal: Courage and camaraderie

The operation in 1972 prepared us for the Yom Kippur War a year later • The story of the infiltration deep into Egyptian territory and the mine that changed all of our plans.

Load more...