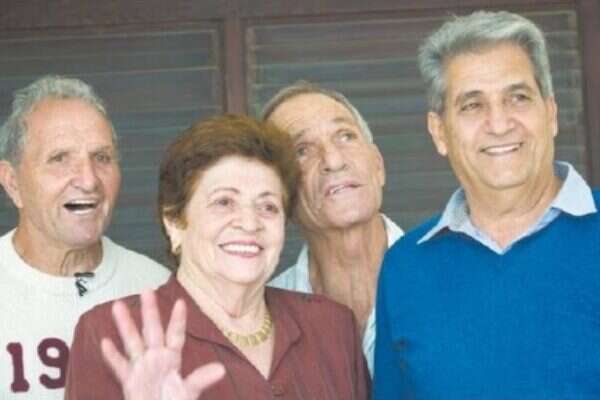

It was another cold night in Bergen-Belsen in autumn 1944. The Nazi death machines campaign to destroy the Jewish people was running full steam ahead, and the hundreds of people who crowded into the barracks knew their time was running out. Three eight-month-old baby boys, named Aharon, George and Shalom, were hidden among the blankets and were circumcised. Despite the terrible risk, the mothers went ahead with the circumcisions. At least their sons would die as Jews. Eight baby boys were circumcised in the barracks that night. Rabbi Amos Borba performed the circumcisions, making sure to give the babies plenty of wine so they would sleep for hours without pain. Miraculously, the boys were still alive when the camp was liberated a few months later. Aharon, George and Shalom went their separate ways after the liberation, but fate brought them together once again. They are 68 years old. Aharon Lavie, a renovations contractor, has four daughters and a grandson. George Borba, a former soccer player, has four children and six grandchildren. Shalom Lavie, who worked in diamonds and is now retired, has four children and four grandchildren. But this week, when the three men gathered at Georges home in Tel Avivs Ramat ha-Hayal neighborhood, their eyes shone with excitement, and they looked like children once again. Suddenly I feel young, Shalom said with a laugh. Youve brought me 70 years back in time, said Shoshana Salhov, 75, Aharons older sister. Grandma Shosho, as her grandchildren call her, was the life of the meeting. Only seven years old when it all happened, she is the only one of the group who was old enough to remember the atrocities of the Holocaust and tell about them. From time to time, between stories, she asks the three men beside her whether they remember what she is talking about. Each time, they burst out laughing. How can we remember- they ask. We were babies. I dont remember what I ate yesterday, Shoshana tells them, but Ill never be able to forget what happened there. Many of Libyas Jews, including the Lavie and Borba families, were expelled to Italy during World War II. When Germany occupied Italy, hundreds of Jews were sent to Bergen-Belsen. Although they were given the status of prisoners because they were British subjects, they quickly discovered that such status was worth little. That was how it seemed to Shoshana, now a grandmother of 16. We said goodbye to our father, Eliyahu, who stayed behind in Italy and joined the British army. My younger brother Aharon, our three older siblings, our mother Mazal and I were sent in freight cars to Bergen-Belsen. I wouldnt leave my mother for a moment. They wore the striped prisoners uniforms with yellow stars. Shalom kept his yellow star. We didnt eat at all the first month, Shoshana recalls. The soup they gave us had worms and snails, and the bread was full of sawdust. But after a few weeks we had no choice because we were hungry and the conditions were horrific. I remember there was a scholarly man with a beard who constantly wrote to the Red Cross. Just two months before liberation, we received packages from them that contained chocolate, cocoa and margarine. We had no idea of the atrocities that were being perpetrated against the Jews of Europe. Shoshana and her older brother Yitzhak missed their father terribly. Their mother, Mazal, gave the camp commander a tongue-lashing, reminding him of the childrens fable about the lion and the mouse. In a moment of weakness or perhaps compassion, he granted her request, and Eliyahu Lavie joined his wife and children in the frozen barracks. Rabbi Amos Borba, a relative of Georges, became the spiritual father of the Jews in the camp. Everyone did whatever he told them, says Shoshana. One day he decided that all the grown-ups should fast, and they did. Later, he told the women to pray a great deal, so they put sheets over their heads and prayed. I remember that as a girl, it looked funny to me when they put the sheets over their heads. And then, one day, the matter of the circumcisions came up. When I grew up, Mother told me about my circumcision ceremony, George recalls. She told me that Id been given so much wine that I slept for two whole days. Ive never been able to drink alcohol since then, he says. Shalom adds, I was told we were all circumcised the same night. Hanukka arrived several weeks after the circumcisions. Eliyahu wanted to observe the holiday properly. Using the packages he had received from the Red Cross, he and his family managed to light the candles. They had a menorah that had been in the family for more than 300 years, and instead of candles, they used margarine. They tore threads from their blankets to use as wicks and put the menorah on the windowsill. But when the Nazis came close, the prisoners quickly pulled on the blanket on which the menorah had been placed and the menorah fell and broke. This week, 68 years later, Aharon and Shoshana brought the menorah to the meeting. They have kept it all these years. Shoshana also made a replica of the menorah, which she uses to light the candles a symbolic, significant act. The presidents heroism Although Aharon Lavie and Shalom Lavie are unrelated by blood, they quickly reunited and grew up together in Netanya. They also played on the Beitar Netanya soccer team, and through the game they heard about George Borba, who had played soccer for Israel for many years. This week, they met him for the first time since their liberation from Bergen-Belsen. With all they have endured, there is one wound that refuses to heal: the lack of public knowledge about the destruction of Libyan Jewry during the Holocaust. When the dictator of Italy, Benito Mussolini, conquered Libya, he instituted anti-Jewish decrees there. He forced Jewish government employees to give up their jobs, barred Jewish children from going to school and expelled anyone who had foreign citizenship. That was how the Lavie and Borba families ended up in Italy and then in Bergen-Belsen. The Jews of Libya were sent to forced-labor camps. Hundreds of them perished. Everybody thinks that the Holocaust was perpetrated only against European Jewry, but thats not true, says Aharon. His sister Shoshana recalls that in 1982, when her granddaughter, then in the eleventh grade, said her grandmother was a Holocaust survivor, the teacher would not believe her and embarrassed her in front of the whole class. Its amazing that even teachers in Israel dont know history, she says sadly. Aharon adds, Even now, not much is known about what Libyan Jewry suffered during the Holocaust. But things are different now. Yad Vashem interviewed Libyan survivors and took their testimonies, and the names of those who perished, the survivors and the members of their families are listed in Bergen-Belsen. When my grandchildren went on a tour of Poland and Germany and saw my name at Bergen-Belsen, they got excited and called me, Aharon says. A few years ago, Shoshana was invited for a formal visit to the office of the social affairs minister at the time, Yitzhak Herzog. It was his father, former president Chaim Herzog, who had saved her life. When the Jewish Brigade came to liberate us, they put all of us on trucks. I was a little girl among the grown-ups, and they forgot about me. Another soldier, who was very tall, picked me up and threw me to my mother, who was on the truck. Only years later, I found out that the soldier had been the late Chaim Herzog. Its thanks to him that I have children and grandchildren. Shoshana had another exciting moment when she gave a lecture to a group of soldiers, including her granddaughter, at the Tzrifin army base. When I arrived at the base, I found myself standing in front of a gate and a fence. But this time, instead of the Nazi skull, the fence had an Israeli flag and the emblem of the IDF. I heard the story of the dramatic circumcision in Bergen-Belsen by accident. At Ulpanat Tzvia, a religious girls middle school and high school in Herzliya, the pupils do a project about the Holocaust every year. They interview survivors and do research. Last year, the teachers, led by the coordinator of the schools history department, Sarit Shavit, focused on the destruction of Libyan Jewry during the Holocaust a topic that has received little recognition or publicity. At the time, Aharon Lavie was renovating the home of the school principal, Rabbi Baruch Frazin. During a conversation with the rabbi, he told his story. To this day, when people talk about the Holocaust and Libyan Jewry, the first thing they ask is what the two have to do with each other, says Rabbi Frazin. It was Shoshana Badash, Georges sister, who discovered the connection between her brother, Aharon and Shalom. She learned that another Holocaust survivor who had been circumcised that same night was living in Italy. The group tried to contact him, but without success. They are now searching for the four other baby boys who were circumcised that night. If you were there or know anyone who was, please contact Sarit Shavit at 050-659-6984 or email her at tzviyam@neto.net.il.

A night to remember

In the autumn of 1944, eight Jewish babies were secretly circumcised in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp • Despite the terrible risk, the mothers went ahead with the circumcisions so that at least their sons would die as Jews • Now, 70 years later, three of the boys who survived reunite, and start the search for the fates of the other five.

Load more...